Many people, familiar with the widely-accepted notion that risk and return go together, are unaware that this formulation is both incomplete and misleading. Let me restate it thus: “Return equals risk which doesn’t equal return.” Obviously, an explanation is in order.

Return equals risk. Almost certainly, someone earning very high returns has run very high risks to do so, though it may not be obvious in hindsight. Indeed, many people who become phenomenally wealthy, not just well-off, took incredible risks and happened to get lucky. Countless others took similar risks that didn’t work out. This second group is more representative of what will likely happen, but the first group is featured more in the media. In other words, we hear much more about lottery winners and dot com millionaires than we do about people who consistently saved and invested over long periods of time or even about people who lost everything attempting to win big. The savers, however, are much more likely to become financially independent than those who took outsized risks. The fact remains though: to earn higher returns, you must accept more risk.

Risk doesn’t equal return. We need to differentiate between “good” risks and “bad” risks. In the financial field, these are known as systematic and unsystematic risks. Systematic risks are “good” – they have higher expected returns and are prudent. Unsystematic risks are “bad” – they have lower expected returns than indicated by the level of risk, and they are imprudent. An example of a systematic risk would be investing in a diversified portfolio of stocks rather than keeping all of your money in CDs. An unsystematic risk would be purchasing one stock instead of the entire portfolio. The expected return increases when purchasing stocks instead of keeping money in CDs. In other words, on average you will do better with the stocks.

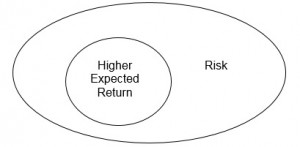

Conversely, purchasing one stock instead of the portfolio has much higher risk, but the expected return is the same. Similarly, most gambling is not prudent because, while the risk of loss is high, the expected level of return is actually negative! The average return on lottery tickets is about 50 cents per dollar spent and the return in casinos is about 85 cents on the dollar (varying widely depending on the game). In other words, every time you spend a dollar playing the lottery you lose, on average, 50 cents. To recap, you generally can’t get higher returns without higher risk, but you absolutely can get high risk without higher returns. Here is the Venn diagram:

Gambling vs. Investing vs. Insurance. Many people mistakenly think there is no difference between gambling and investing or gambling and insurance. It is true there are some similarities in that they all are associated with chance occurrences, but there are significant differences as well. These “products” will impact a financial plan in three aspects. People generally prefer: higher returns, lower risks, and a higher probability of meeting lifetime financial goals. Using these products as they are designed to be used, we get these results:

| Activity | Return | Risk | Source of Risk | Increased Financial Success |

| Insurance | Lower | Lower | Inherent in Life | Yes |

| Investments | Higher | Higher | Inherent in Business | Yes |

| Gambling | Lower | Higher | Artificially Created | No |

As you can see, none of the products give us positive effects in all areas. In other words, as we have been stressing, you can’t get higher returns and lower risks simultaneously. Note, though, insurance can reduce certain risks and thus help achieve financial success; investments can increase expected returns and also help achieve financial success. Gambling has no such redeeming characteristics. Further, investments and insurance merely redistribute existing risk to those willing and able to bear it (for a price), gambling involves creating risk where none existed before the wager was made.

How Much? There is actually a process to determine what level of risk and return is appropriate for a particular situation. Financial plans should be designed to yield the highest level of happiness possible across all possible future scenarios. Taking prudent risks that raise the probability of reaching financial goals is generally appropriate, and taking actions that decrease the probability of financial success is unwise.