|

Financial Professionals Winter 2021

This is my quarterly missive intended primarily for my fellow financial professionals wherein I share items I have run across or thought about this quarter which I think might be beneficial to you. Enjoy!

We have capacity for a few more consulting clients (typically RIA firms). The annual retainer for this is generally the square-root of your AUM (with a minimum of $10,000 and maximum of $50,000). For more details or to discuss further, please e-mail or call me at 770-517-8160. – David

First, see Dan Solin, and Jim Rohrbach, and Josh Brown for good articles on connecting with clients. (I also highly recommend How to Win Friends and Influence People – not that I am very good at anything in the book!) In addition this is on point, though from a very different area.

Second, is value investing still viable? See Resurrecting the Value Premium. But sometimes a story is better than data.

Third, “While the top 1% of Americans have a combined net worth of $34.2 trillion, the poorest 50% – about 165 million people – hold just $2.08 trillion, or 1.9% of all household wealth.” (source)

That means half of the folks have a net worth of just under $13,000. I’m sorry, but that’s not even trying.

Related, there’s a good recap of the highlights of the most recent SCF from the always excellent Jonathan Clements here.

Fourth, the NAPFA message boards had a thread concerned about the 4% rule. I thought my comments might be worth sharing here too:

That’s a great question. (Is there a “reasonably high possibility that US stock returns from 2000-2029 will under-perform what is currently the worst-ever 30-year period, which started in 1929 – and that’s even if U.S. stocks average 10+% per year over the remainder of this decade.”) So I took a look at the data.

To worry about a historically terrible 30-years, we should be currently in one of the worst 20-year periods I would think. I took monthly data for the total U.S. stock market (CRSP 1-10), 5-year Treasurys, and CPI from 1/1/1926 to 8/31/20 (CPI data not out yet for September). There are 885 rolling 20-year periods (using monthly data, so there is lots of overlap). The worst ones for stocks are periods ending in 1947-1951, we do pick up some periods ending in 2020 starting at number 48 (the 3/31/20 period had a CAGR of just 5.80%). So that 20-year period is just outside the bottom 5% of historical periods.

But our concern on withdrawals is not nominal rates, but real rates. So I adjusted for CPI and reranked the data. Now the worst 20-year periods are those ending in most months of 1982 and we pick up lots of late 1970’s and various periods in the 1980’s right below those. A period ending in 2020 doesn’t put in an appearance until number 160 (3/31/20 again with a real CAGR of just 3.57%). That is in the worst 18% (-ish) of real 20-year returns. So we’re in the bottom quintile, but certainly not the bottom.

Of course, we don’t (I hope!) have clients in all stock portfolios, so I looked at a nominal 60/40 portfolio (CRSP 1-10 and 5-year Treasurys). Now the worst 20-year periods are back to those ending in the 1947-1951 range. The first 2020 period is (again) 3/31/2020 at number 47 with a return of 5.47%. So that is again just outside the worst 5% of historical periods.

Finally, (I’m sure you can predict this next iteration) let’s look at real 60/40. We’re back to periods in the early 1980’s being the worst ones. 3/31/2020 puts in an appearance at number 209, so about the bottom quarter of historical results. Bad, but probably not warranting panic. Of course the expected returns on stocks and bonds were much higher (valuations lower) in the early 1980’s than they are today so perhaps this will be a historically poor period, but perhaps not. Remember our poorest recent period ended 3/31/2020 and we have already had a nice bounce from there. The 20-year real return on 60/40 through 8/31/2020 was 4.51% which is at about the 35% level of historical periods.

There are two other reasons for some optimism. While, from current levels, U.S. large and fixed income have very low expected nominal returns the expected real returns are less low. In addition, foreign stocks and value tilts have much more attractive expectations. Since your client portfolios should have at least the foreign exposure (if not the value), you might expect a not-too-shabby future (though perhaps not great).

To get back to the original question. If stocks averaged 10% over the rest of the decade, and inflation is 2% (the Fed target, the TIPS spread is actually below that), that would imply real returns of about 8% (technically 7.84%). Since the real returns for the first 20 years are about 4% (depending on when we start and stop the rolling 20 years) we would have roughly (1.04^20*1.08^10)^(1/30)-1= 5.3% real CAGR for 30 years on stocks. That would be in the bottom 16% or so of historical 30-year runs. (And adding bonds at current yields don’t help.) Since 8% real seems heroic to expect (to me anyway) it does seem we are in a bad period, but not (again IMHO) so bad that the 4% rule is useless.

Also remember that things looked dire on valuations when Greenspan gave his “irrational exuberance” speech in December 1996. Real U.S. stock returns from 1/1997 to 8/31/2020 have been 6.8% annualized (9% nominal).

Fifth, expanding on the previous point (consistent with my penchant for over-analyzing everything), I decided to see what the current portfolio value and withdrawal rate would be on 8/31/2020 if someone started with $1,000,000 portfolio in 2000 and used the 4% rule. I rebalanced monthly and also increased the initial draw monthly with CPI. This should be conservative, because in real life people don’t increase that frequently, there tends to be a lag in their withdrawals to match inflation. I used several start dates to be sure the results were robust. As a reminder, the stocks are CRSP 1-10 (i.e. total US market) and the bonds are 5-year Treasurys. (No, that isn’t a typo.)

A 60/40 portfolio for a retiree that started draws on these dates would have these figures on 8/31/2020:

60/40 |

Start Date |

Current Value |

Current Draw |

Withdrawal Rate |

12/31/1999 |

$1,017,658 |

$5,148 |

6.1% |

3/31/2000 |

$981,404 |

$5,061 |

6.2% |

6/30/2000 |

$1,111,064 |

$5,025 |

5.4% |

Given that our retiree (if they were 65 at retirement) is now 85, those seem like reasonable withdrawal rates at this point. This does not seem like failure is likely. Indeed, if the portfolio just matches inflation from this point it will last another 16+ years!

What if our retiree was crazy aggressive and did 100% stocks?

All Stock |

Start Date |

Current Value |

Current Draw |

Withdrawal Rate |

12/31/1999 |

$502,489 |

$5,148 |

12.3% |

3/31/2000 |

$451,502 |

$5,061 |

13.5% |

6/30/2000 |

$703,344 |

$5,025 |

8.6% |

Ouch. And THAT, my friends, is why we diversify! (Though I should note, this might also work – but it’s pretty iffy. No real return from this point forward means the portfolio would expire in 7 years for the 3/31/2000 retiree. That would be age 92. Positive real returns would, of course, extend that somewhat, but our 3/31/2000 retiree is likely toast if he/she lives to 95.)

This is why I have told CFP classes, etc. for years that the “4% rule” is for portfolios that are predominately, but not exclusively, stocks. I.e. from 50/50 to 90/10 you are probably ok, and from 60/40 to 80/20 you are almost certainly (not completely certain, we don’t have that option) ok.

Sixth, friends don’t let friends buy alts…

Seventh, what to do in a low return environment? I have touched on this before (here for example), but it seems like it might be time again.

If returns are lower than they were in the past, but risks are the same (i.e. the return per unit of risk is now lower), there are three perfectly rational responses:

- Keep your portfolio the same but realize you will not get the returns you once did with that portfolio.

- Decrease the risk in your portfolio. Since you are not getting paid as much for taking risk you decide to take less of it.

- Increase the risk in your portfolio. Since you desire a certain level of return the only way to get it is to increase risk.

Now, the problem is that although the options above are opposed to each other, they all make sense and are rational. But we have to pick one.

I don’t have a simple answer for you though. I think it depends on the client’s resources compared to their needs. For example, if a client is wealthy (compared to their needs, not in absolute terms) the correct choice is probably different from a client who is not at all wealthy (again, relative to need). For example, suppose we have three families, each newly retired, and each need $60,000/year. Social Security/pensions/whatever are expected to provide $20,000. That means $40,000 must be provided by the portfolio. One client has an $800,000 portfolio; one has $1,000,000 portfolio; and one has a $1,200,000 portfolio.

- The family with the $800,000 should probably have a slightly more aggressive portfolio than they would have in a higher return environment.

- The family with the $1,000,000 should probably have the same portfolio they would have in a higher return environment.

- The family with the $1,200,000 should probably have a slightly less aggressive portfolio than they would have in a higher return environment.

I think. This answer is tentative, provisional, and preliminary!

Eighth, There’s a good article on QLACs here. While I’m not a fan of variable or equity-indexed annuities (to put it mildly), I do in theory like SPIAs (but not at current interest rates) and I like QLACs even more – but again, in theory. I don’t think the pricing is very good and I would very much like to see an inflation-adjusted QLAC.

Ninth, here’s the 13-point checklist Google uses to find and promote its best leaders (source):

- I would recommend my manager to others

- My manager assigns stretch opportunities to help me develop my career

- My manager communicates clear goals

- My manager regularly gives me actionable feedback

- My manager provides the autonomy I need to do my job (doesn’t micromanage)

- My manager consistently shows consideration for me as a person

- My manager keeps the team focused on priorities, even when it’s difficult (e.g. declining or deprioritizing other projects)

- My manager makes tough decisions effectively

- My manager shares relevant information from his/her boss(es)

- My manager has had a meaningful discussion with me about my career development in the past six months

- My manager has the expertise required to effectively manage me

- The actions of my manager show he/she values my perspective (even if different from his/hers)

- My manager effectively collaborates across boundaries

Tenth, with possible changes in the unified credit coming with Democrats in charge, it might be time for a short Estate Tax Planning 101 refresher if you need it. Also, this didn’t pass, but it is a good example of things that may happen in the future with retirement plans. (More here and here too.) Big changes (to me) are:

- increase in RMD age to 75 from 72

- increase of catch-up from $6,500 to $10,000 at age 60.

- Change QLAC limit to $200k and addition of spousal benefits

- RMD penalty reduced to 25% (or 10% if timely corrected) from 50%

- QCDs raised to $130k from $100k and expanded to qualified plans (currently only IRAs are eligible)

Finally, here’s a paper on wealth taxes in case we start to move that direction.

Eleventh, as financial advisors, our “product” is really wisdom (as I’ve said before), and it turns out we are wiser about other people’s situations than we are our own. This has two implications, 1) our clients (even our very wise clients) need us, and 2) we need wise advisors ourselves (or strategies to get distance on our issues) no matter how wise we consider ourselves to be. (I’m blessed to have Anitha.) From Aeon:

… When inspecting the results, scholars observed a peculiar pattern: for most characteristics, there was more variability within the same person over time than there was between people. In short, wisdom was highly variable from one situation to the next. The variability also followed systematic rules. It heightened when participants focused on close others and work colleagues, compared with cases when participants focused solely on themselves.

These studies reveal a certain irony: in those situations where we might care the most about behaving wisely, we’re least likely to do so. Is there a way to use evidence-based insights to counter this tendency?

My team addressed this by altering the way we approach situations in which wisdom is heightened or suppressed. When a situation concerns you personally, you can imagine being a distant self. For instance, you can use third-person language (‘What does she/he think?’ instead of ‘What do I think?’), or mentally put some temporal space between yourself and the situation (how would I respond ‘a year from now’?). Studies show that such distancing strategies help people reflect on a range of social challenges in a wiser fashion. In fact, initial studies suggest that writing a daily diary in a distant-self mode not only boosts wisdom in the short term but can also lead to gains in wisdom over time. The holy grail of wisdom training appears one step closer today.

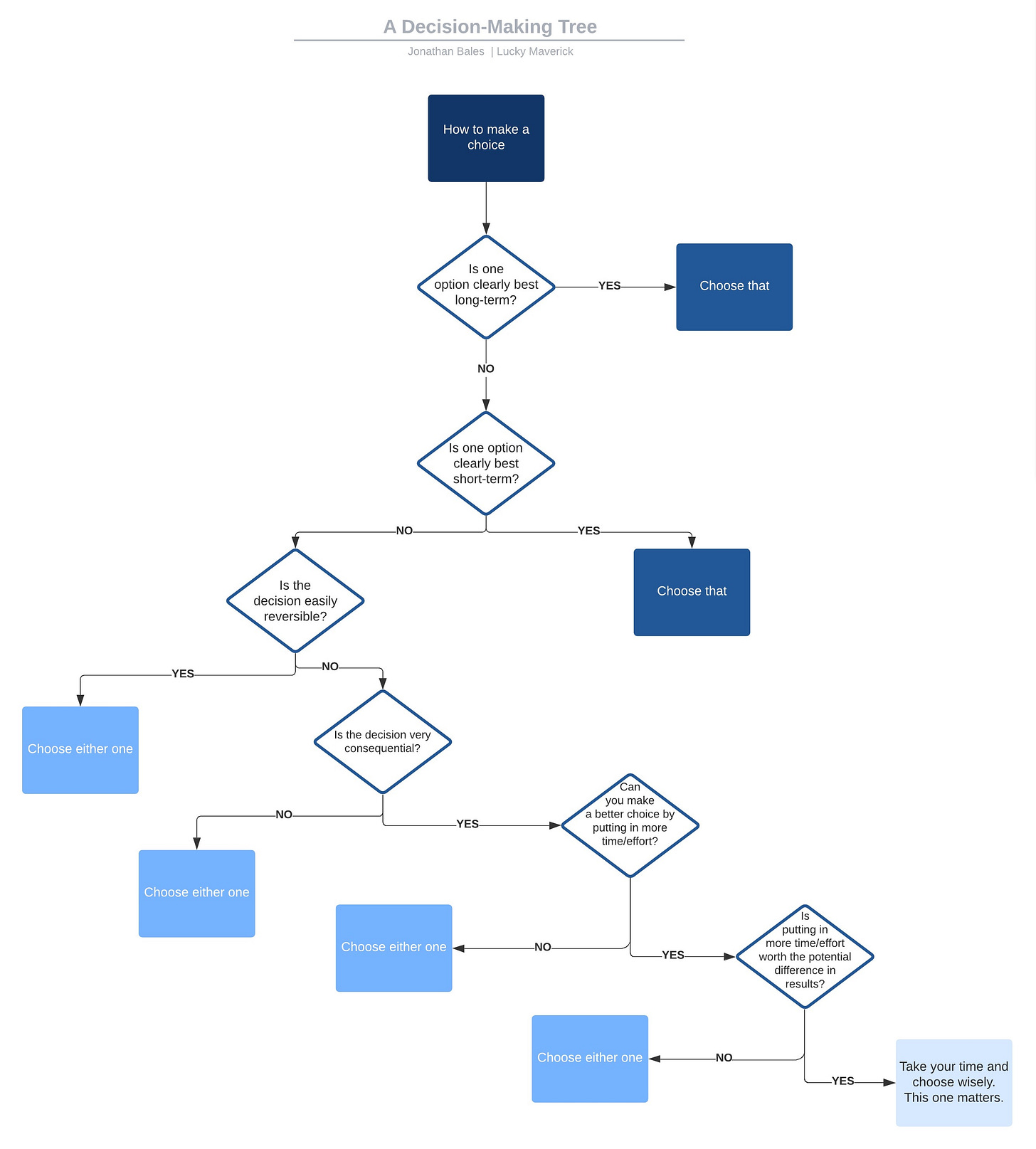

Related, here's an excellent decision-making flowchart:

Also, you may be able to get the wisdom of crowds … without the crowd, as shown in this paper. Here’s the abstract:

Many decisions rest upon people’s ability to make estimates of some unknown quantities. In these judgments, the aggregate estimate of the group is often more accurate than most individual estimates. Remarkably, similar principles apply when aggregating multiple estimates made by the same person – a phenomenon known as the “wisdom of the inner crowd”. The potential contained in such an intervention is enormous and a key challenge is to identify strategies that improve the accuracy of people’s aggregate estimates. Here, we propose the following strategy: combine people’s first estimate with their second estimate made from the perspective of a person they often disagree with. In five pre-registered experiments (total N = 6425, with more than 53,000 estimates), we find that such a strategy produces highly accurate inner crowds (as compared to when people simply make a second guess, or when a second estimate is made from the perspective of someone they often agree with). In explaining its accuracy, we find that taking a disagreeing perspective prompts people to consider and adopt second estimates they normally would not consider as viable option, resulting in first- and second estimates that are highly diverse (and by extension more accurate when aggregated). However, this strategy backfires in situations where second estimates are likely to be made in the wrong direction. Our results suggest that disagreement, often highlighted for its negative impact, can be a powerful tool in producing accurate judgments.

Finally, from Annie Duke:

Twelfth, here’s a good interactive graph of home price changes.

Thirteenth, even though stock valuations look elevated, when compared to real interest rates they are still attractive – particularly outside the U.S. as seen in this from Barclays. (I’m less interested in the COVID aspects of the paper.) See current value of the gray line on figure two (at least I think it’s gray, I’m colorblind).

Fourteenth, “impact investing” isn’t a new thing. From The Economist, 1908 (source):

Fifteenth, we sent this out to our clients a few months ago:

I have read hundreds of books on financial planning and investing, but only a few stand out. They do so because they made crucial points in engaging ways. Those books are:

- Winning the Loser’s Game, by Charles Ellis – first published as a short article in the Financial Analysts Journal in 1975, this book eloquently makes the point that sometimes it’s better to play not to lose rather than play to win.

- The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas Stanley and William Danko – first published in 1996, the examples are now dated, but the lessons are timeless. The main lesson being: there is a vast difference between income and wealth though they are frequently confused.

- The Four Pillars of Investing by William Bernstein – first published in 2002, it discusses the theory, history, psychology, and business of investing. When this book came out, I was irritated. The crucial insights that I had amassed through hundreds (if not thousands) of hours of reading market history and academic finance papers was captured and summarized in one readable volume.

To this list I now add a fourth book: The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel which just came out. The best way to describe this book is with an excerpt from the introduction:

My favorite Wikipedia entry begins: “Ronald James Read was an American philanthropist, investor, janitor, and gas station attendant.”

Ronald Read was born in rural Vermont. He was the first person in his family to graduate high school, made all the more impressive by the fact that he hitchhiked to campus each day.

For those who knew Ronald Read, there wasn’t much else worth mentioning. His life was about as low key as they come.

Read fixed cars at a gas station for 25 years and swept floors at JCPenney for 17 years. He bought a two-bedroom house for $12,000 at age 38 and lived there for the rest of his life. He was widowed at age 50 and never remarried. A friend recalled that his main hobby was chopping firewood.

Read died in 2014, age 92. Which is when the humble rural janitor made international headlines.

2,813,503 Americans died in 2014. Fewer than 4,000 of them had a net worth of over $8 million when they passed away. Ronald Read was one of them.

In his will the former janitor left $2 million to his stepkids and more than $6 million to his local hospital and library.

Those who knew Read were baffled. Where did he get all that money?

It turned out there was no secret. There was no lottery win and no inheritance. Read saved what little he could and invested it in blue chip stocks. Then he waited, for decades on end, as tiny savings compounded into more than $8 million.

That’s it. From janitor to philanthropist.

A few months before Ronald Read died, another man named Richard was in the news.

Richard Fuscone was everything Ronald Read was not. A Harvard-educated Merrill Lynch executive with an MBA, Fuscone had such a successful career in finance that he retired in his 40s to become a philanthropist. Former Merrill CEO David Komansky praised Fuscone’s “business savvy, leadership skills, sound judgment and personal integrity.” Crain’s business magazine once included him in a “40 under 40” list of successful businesspeople.

But then … everything fell apart.

In the mid-2000s Fuscone borrowed heavily to expand an 18,000-square foot home in Greenwich, Connecticut that had 11 bathrooms, two elevators, two pools, seven garages, and cost more than $90,000 a month to maintain.

Then the 2008 financial crisis hit.

The crisis hurt virtually everyone’s finances. It apparently turned Fuscone’s into dust. High debt and illiquid assets left him bankrupt. “I currently have no income,” he allegedly told a bankruptcy judge in 2008.

First his Palm Beach house was foreclosed.

In 2014 it was the Greenwich mansion’s turn.

Five months before Ronald Read left his fortune to charity, Richard Fuscone’s home—where guests recalled the “thrill of dining and dancing atop a see-through covering on the home’s indoor swimming pool”—was sold in a foreclosure auction for 75% less than an insurance company figured it was worth.

Ronald Read was patient; Richard Fuscone was greedy. That’s all it took to eclipse the massive education and experience gap between the two.

The lesson here is not to be more like Ronald and less like Richard—though that’s not bad advice.

The fascinating thing about these stories is how unique they are to finance.

In what other industry does someone with no college degree, no training, no background, no formal experience, and no connections massively out-perform someone with the best education, the best training, and the best connections?

I struggle to think of any.

It is impossible to think of a story about Ronald Read performing a heart transplant better than a Harvard-trained surgeon. Or designing a skyscraper superior to the best-trained architects. There will never be a story of a janitor outperforming the world’s top nuclear engineers.

But these stories do happen in investing.

The fact that Ronald Read can coexist with Richard Fuscone has two explanations. One, financial outcomes are driven by luck, independent of intelligence and effort. That’s true to some extent, and this book will discuss it in further detail. Or, two (and I think more common), that financial success is not a hard science. It’s a soft skill, where how you behave is more important than what you know.

I call this soft skill the psychology of money. The aim of this book is to use short stories to convince you that soft skills are more important than the technical side of money. I’ll do this in a way that will help everyone—from Read to Fuscone and everyone in between—make better financial decisions.

These soft skills are, I’ve come to realize, greatly underappreciated.

Finance is overwhelmingly taught as a math-based field, where you put data into a formula and the formula tells you what to do, and it’s assumed that you’ll just go do it.

This is true in personal finance, where you’re told to have a six-month emergency fund and save 10% of your salary.

It’s true in investing, where we know the exact historical correlations between interest rates and valuations.

And it’s true in corporate finance, where CFOs can measure the precise cost of capital.

It’s not that any of these things are bad or wrong. It’s that knowing what to do tells you nothing about what happens in your head when you try to do it.

We highly recommend this book. If you are a current wealth management client of Financial Architects and would like a copy, simply let us know and we’ll be happy to send you one.

Sixteenth, in many books and articles (such as Progress) the decline of the murder rate over time is shown as progress; here’s a graph from the interwebs:

But, (and I regret I never thought of this) it appears much of that (at least the recent portion) is improvement in medicine rather than decline in violence, see here.

Seventeenth, the answers to tough questions always consist of three words:

Before you get a CFP/CPA/JD/etc.: “I don’t know”

After you get a CFP/CPA/JD/etc.: “Well it depends”

Eighteenth, J.P. Morgan’s updated Capital Markets Assumptions are out.

Nineteenth, investing is hard, because you need to answer these questions:

- Am I being disciplined or stubborn?

- Am I being foolish or staying ahead of the curve?

- How useful is market history?

- What if it really is different this time?

- Do I have enough?

See also:

As Voltaire observed, “Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.”

Twentieth, I recently read Confusion de Confusiones. It’s (from the introduction), “a book written in Spanish by a Portuguese Jew, published in Amsterdam, cast in dialogue form, embellished from start to finish with biblical, historical, and mythological allusions, and yet concerned primarily with the business of the stock exchange and issued as early as 1688.”

Here are four principles of speculation (page 10):

The difficulties and the frightful occurrences in the exchange business have taught some precepts.

The first principle in speculation: Never give anyone the advice to buy or sell shares, because where perspicacity is weakened, the most benevolent piece of advice can turn out badly.

The second principle: Take every gain without showing remorse about missed profits, because an eel may escape sooner than you think. It is wise to enjoy that which is possible without hoping for the continuance of a favorable conjuncture and the persistence of good luck.

The third principle: Profits on the exchange are the treasures of goblins. At one time they may be carbuncle stones, then coals, then diamonds, then flint stones, then morning dew, then tears.

The fourth principle: Whoever wishes to win in this game must have patience and money, since the values are so little constant and the rumors so little founded on truth. He who knows how to endure blows without being terrified by the misfortune resembles the lion who answers the thunder with a roar, and is unlike the hind who, stunned by the thunder, tries to flee. It is certain that he who does not give up hope will win, and will secure money adequate for the operations that he envisaged at the start. Owing to the vicissitudes, many people make themselves ridiculous, because some speculators are guided by dreams, others by prophecies, these by illusions, those by moods, and innumerable men by chimeras.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose…

They even had TINA, anchoring, and recency biases in 1688 (page 13):

The rate of interest on ordinary loans amounts to only 3 per cent per year, and, if the creditor receives security, to only 2½ per cent. Therefore, even the wealthiest men are forced to buy stocks [TINA], and there are people who do not sell them when the prices have fallen, in order to avoid a loss [anchoring]. But they do not sell at rising prices either, because they do not know a more secure investment for their capital [recency].

And from page 14 we have the 1688 version of the adage “buy the rumor, sell the news” of modern times: “The expectation of an event creates a much deeper impression upon the exchange than the event itself.”

[I’ll also note here that the recent fervor for SPACs isn’t new either. During the South Sea Bubble (1720) money was raised with this famous (or infamous) line: “For carrying-on an undertaking of great advantage but no-one to know what it is!!” That is exactly the SPAC pitch.]

Twenty-first, a reporter queried, “What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?” My response:

When I was in my early 20’s I was acquainted with a successful businessman who was about 30 years older. Apparently I was visibly impressed with his home, car, etc. so he gave me the best words of wisdom I have ever heard, “David, you seem impressed by the trappings. You need to realize that everyone has the same financial problems – the decimal point just moves over. I worry about making $300,000 next year (roughly $600,000 in today's dollars) just like you probably worry about making $30,000. It takes me every bit of that to support my living expenses.”

Twenty-second, hypocrisy from politicians in a pandemic isn’t new either, see the “Double Standards” section of this page.

Twenty-third, good roundup of research on stock-picking here.

Twenty-fourth, the limit to leverage explanation for the low-vol anomaly has been the best so far, but this co-skewness argument is interesting and here’s an argument that value is really sort of anti-momentum

Twenty-fifth, from CityWire:

See what you make of this:

A common view of retail finance is that conflicts of interest contribute to the high cost of advice. Within a large sample of Canadian financial advisors and their clients, however, we show that advisors typically invest personally just as they advise their clients. Advisors trade frequently, chase returns, prefer expensive and actively managed funds, and underdiversify. Advisors’ net returns of -3% per year [as compared to “passive benchmarks”] are similar to their clients’ net returns. Advisors do not strategically hold expensive portfolios only to convince clients to do the same; they continue to do so after they leave the industry.

That’s the abstract of a paper by professors Juhani Linnainmaa, Brian Meltzer and Alessandro Previtero that was recently published in the influential Journal of Finance.

The paper’s title, ‘The Misguided Beliefs of Financial Advisors,’ highlights what makes the authors’ views unique:

[Advisors] recommend frequent trading and expensive, actively managed products because they believe that active management dominates passive management, despite evidence to the contrary. These advisors, who we refer to as having misguided beliefs, are willing to hold the investments they recommend… Yet they realize net returns substantially below passive benchmarks, both for clients and themselves. Eliminating conflicts of interest may therefore reduce the cost of advice by less than policymakers hope…. Improving their advice would therefore require changing their beliefs.

Already I can hear advisors protest that their beliefs are not, in fact, misguided. For instance, while the academic consensus may be that passive fund performance must be superior to active fund performance, there are those who argue that the flow of money into passive funds has skewed performance figures, and active funds will somehow perform better going forward. (The passive advocates would retort that this is impossible, since the average active return must equal the passive return less fees; let’s avoid rehashing the whole debate here.)

Either way, the authors are aware that a regulatory regime will find it much harder to ‘correct’ beliefs that are ‘wrong’ rather than to simply buff away conflicts. Such a regime would place regulators in the awkward position of deciding what constitutes ‘good advice’ and then ensuring that advisors hold these beliefs. Instead of policing conflicts, they need to fight Thoughtcrime.

But let’s set Orwell aside for a moment. Because the professors’ underlying point may reveal a potential weakness in the mental models we’re currently using.

The common perception that conflicts of interest are responsible for inferior advice itself rests upon the belief that the underlying skill of financial advisors is strong. This paper suggests a simpler theory, which effectively amounts to Hanlon’s razor – ‘Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity’ – for financial advisors.

Whether this conclusion is uplifting or dispiriting I will leave up to the reader. On one hand, it would mean that advisors aren’t maliciously fleecing their clients. On the other, it suggests that advisors aren’t as smart as we may have thought. The problem isn’t that the light is being shrouded by the veil of conflict – it’s that the bulb is not particularly bright.

However, there may be a slightly more optimistic way to interpret these findings. If ‘science progresses one funeral at a time,’ then perhaps advisors’ beliefs progress one business model at a time.

That is: It may be true that the advisors studied wholeheartedly believe that the financial decision that brought the advisor (and the advisor’s firm) the most money was also the best one for the client. (You could chalk it up to highly effective corporate training, a personal need to tamp down cognitive dissonance, or simply the prevalence of now-outdated modes of belief.) If this is the case, then it wouldn’t be too surprising to find that even after mainstream beliefs changed, or after the advisors themselves have retired, they found themselves continuing to fight a war that had already been lost – the Japanese holdouts of the wealth world.

But for a new generation forced to put clients’ interests first, there may be no reason to maintain old-fashioned beliefs about, say, the wisdom of buying an expensive mutual fund after a period of strong performance. Perhaps a new culture will take hold.

If advisors do indeed hold ‘misguided beliefs,’ then let’s hope that they are just that – misguided. With new guides will come, one hopes, new beliefs as well.

Twenty-sixth, here’s a good corporate tax overview – just two pages!

Finally, my recurring reminders:

J.P. Morgan’s updated Guide to the Markets for this quarter is out and filled with great data as usual.

Morgan Housel and Larry Swedroe continue to publish valuable wisdom. Just a reminder to go to those links and read whatever catches your fancy since last quarter.

That’s it for this quarter. I hope some of the above was beneficial.

If you are receiving this email directly from me, you are on my list of Financial Professionals who have requested I share things that may be of interest. If you no longer wish to be on this list or have an associate who would like to be on the list, simply let me know.

We have clients nationwide; if you ever have an opportunity to send a potential client our way that would be greatly appreciated. We also have been hired by some of our fellow advisors as consultants to help where we can with their businesses. If you are interested in learning more about that arrangement, please let us know.

We also offer a monthly email newsletter, Financial Foundations, which is intended more for private clients and other non-financial-professionals who are interested. If you would like to be on that list as well, you may edit your preferences here.

Finally, if you have a colleague who would like to subscribe to this list, they may do so from that link as well.

Regards,

David

Disclosure

|