|

Financial Professionals Fall 2020

This is my quarterly missive intended primarily for my fellow financial professionals wherein I share items I have run across or thought about this quarter which I think might be beneficial to you. Enjoy!

We have capacity for a few more consulting clients (typically RIA firms). The annual retainer for this is generally the square-root of your AUM (with a minimum of $10,000 and maximum of $50,000). For more details or to discuss further, please e-mail or call me at 770-517-8160. – David

First, see TL;DR: The Best Finance Books in One Sentence.

Second, I had no idea Chinese government intrusion was this bad.

Third, you have probably seen some analysis of the Biden tax proposals. Here is one from the Tax Foundation and one from EY.

Fourth, if you have a mortgage, refi if you haven’t already and tell your clients the same (FRED graph). I know I said this last quarter, but it’s worth belaboring.

Fifth, I have a game for you. I was thinking that the last 20 years is roughly a clean 2 market cycles. (I.e. in early 2000 I think US, large, growth stocks were also richly valued compared to other asset classes so we are measuring from a top to a top.) Here are 17 asset classes in alphabetical order:

US REIT |

AGG |

EAFE |

EM |

Foreign REIT |

HY |

R1000 |

R1000G |

R1000V |

R2000 |

R2000G |

R2000V |

R3000 |

R3000G |

R3000V |

S&P 500 |

TIPS |

The game is to, without looking at any data, rank them by their total returns (geometric) over the past 20 years (7/2000-6/2020) from highest to lowest. Probably easiest to print this and pick the highest and write a 1 next to it, then the next highest with a 2, etc. I’ll put the actual ranking (and annualized returns) further down so you can see how you did.

Sixth, money (well, income anyway) does buy happiness and there is no tapering off at the high end (source).

Seventh, great tweet:

- Live below your means.

- Invest, diversified, with a 10+ year horizon.

- Expect and accept volatility.

That’s 90% of finance.

(Buy his book too!)

Eighth, I’m sure I’m flogging a deceased equine at this point, but I think it’s important. As someone once said (it’s variously attributed), “The past doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.”

In June 2000 the Russell 3000 Growth Index had outperformed the Russell 3000 Value Index for 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20 years and since inception. There was no time period ending June 2000 (since the Russell index data started in 1979) that value had beat growth. (What growth or value index you use doesn’t matter, the results would be the same regardless I think. I just use the Russell because they were the most commonly used back then and probably still today for something like this.)

In June 2020 the Russell 3000 Growth Index has outperformed the Russell 3000 Value Index for 1, 3, 5, 10 years and barely under for 15 years and not since inception. Here is a chart of the difference in annualized returns for the periods ending in 6/2000 and 6/2020 for the Russell 3000 Value minus the Russell 3000 Growth indexes:

|

Period Ending |

Years |

Jun-00 |

Jun-20 |

1 |

-34% |

-31% |

3 |

-17% |

-17% |

5 |

-10% |

-11% |

10 |

-4% |

-7% |

15 |

-4% |

-5% |

20 |

-1% |

1% |

Inception |

-1% |

0% |

Negative numbers mean growth was beating value. Those are remarkably similar performance differences in the two periods!

Let’s roll ahead just 12 months and add the period ending June 2001:

|

Period Ending |

|

Jun-00 |

Jun-20 |

Jun-01 |

Jun-21 |

1 |

-34% |

-31% |

47% |

? |

3 |

-17% |

-17% |

5% |

? |

5 |

-10% |

-11% |

3% |

? |

10 |

-4% |

-7% |

2% |

? |

15 |

-4% |

-5% |

1% |

? |

20 |

-1% |

1% |

2% |

? |

Inception |

-1% |

0% |

2% |

? |

Just 12 months, when value beat growth by 47%, changed the winner from growth to value across the board. Now, I’m not predicting the next twelve months will duplicate that, but it isn’t impossible either.

Similar analysis, but with longer and different data, here.

Ninth, ignore mutual fund performance: Carhart (1997) Mutual Fund Performance Persistence Disappears Out of Sample

Carhart found limited persistence, but it looks like it started going away circa 1980 and was gone in data after that used in the paper (1994).

(The persistence was explained by momentum in the underlying holdings – there never was persistence after adjusting for a four-factor exposures. High expense ratios can cause persistence in loser funds though.)

Tenth, a good list of tips for prospect meetings (among other interactions) from an unexpected source, here.

Eleventh, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. This is from The Spectator, November 29, 1890 (source):

Moreover, the number of small speculators is increasing also. This is partly the result of the fall in the rate of interest, which tempts men otherwise averse from risk to improve their incomes; partly of the very decided increase in the habit of betting, which extends itself to everything; and partly of the more general diffusion of a kind of financial knowledge, derived, we fear, very often from no better source than the financial newspapers which spring up every day in London, and are by no means all to be trusted even for common honesty in offering their “opinions.” The temptation to speculate is, indeed, very great.

Does that not sound like a description of Robinhood investors today?

Twelfth, this isn’t useful, just interesting: Dow Jones’s 22,000 Point Mistake

Thirteenth, there is a lot of discussion these days about the inequality in wealth and income between various groups, and whether it is increasing. Here is an interesting paper about the cultural revolution in China (free version). As you may know, the educated/skilled/wealthy folks had their wealth confiscated, were required to work in the fields, couldn’t educate their children, etc. There really was (an appalling) “leveling” of society. And the children of those (formerly) higher SES (socio-economic-status) folks did worse than others. But the grandchildren – when economic freedom returned – did better than most. Because taking away all the money, the jobs, the education, etc. didn’t take away the values and family culture.

From the abstract: “Through intergenerational transmission, socioeconomic conditions and cultural traits thus survived one of the most aggressive attempts to eliminate differences in the population and to foster mobility.”

So, that implies that even if you confiscated all the wealth and redistributed it evenly, and gave everyone free (and equivalent) education opportunities, the descendants of the current high-SES folks would be high-SES again. What are the traits that breed success? From the paper: “[The grandchildren of the elites] are less averse to inequality, more individualistic, more pro-market, more pro-education, and more likely to see hard work as critical to success.”

Fourteenth, Working Longer Solves (Almost) Everything is a paper (here) which Larry Swedroe reviewed on Advisor Perspectives (here).

While most of the paper is technically true, most of it is also misleading. Of course working longer would solve many problems; if people would just work up until they died there would be no retirement income shortfalls, we could eliminate Social Security, etc. But of course that is silly.

I’m not taking time to research all the issues to debunk with sources, but here are the items that I’m pretty sure are misleading:

- “According to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics data, based on 2016 figures, ‘older households’ - defined as those headed by someone 65 and older - spend an average of $45,756 per year, or roughly $3,800 a month. That’s about $1,000 less than the monthly average spent by all US households combined (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2017).” But the average size of the household over 65 is smaller too! Spending less does not necessarily mean that spending is constrained (though that appears to be the implication here).

- “Assuming retirement at 65, an average person would have to earn nearly 1.5 times his yearly expenditures over the course of a 40-year career in order to save enough to support his 25-year retirement.” That means a savings rate of 33% is required. That is, shall we say, implausible.

- “It has been estimated that 90 percent of Americans begin collecting social security retirement benefits at or before their full retirement age, with the most popular age 62, the earliest eligible age, and the average age to begin receiving benefits 64 (Munnell and Chen 2015).” I’m sure that’s right, but it’s not necessarily related to retirement. Most people take the money early because it’s there and they are not making a wise decision.

- “Employers always are in need of experienced, well-trained, and productive workers. As the overall population ages, the perception of what constitutes ‘working age’ is evolving to include older adults in their late 60s and beyond.” Then obviously the need for age discrimination laws has passed and they should be repealed. In the authors defense, the discussion of costs, etc. does get more nuanced.

- “Older workers also benefit from continued participation in the workforce; work provides a means for older adults to remain engaged in their communities. In addition to reaping economic benefits from employment, they will be healthier for it, less isolated, and happier. Objective social isolation has repeatedly been found to be a risk factor for poor mental and physical health, including higher prevalence of disease and increased risk of mortality (Streeter, et al. 2020).” I don’t know why anyone retires with such benefits from continuing to work (that was sarcasm).

- “Work provides opportunities for learning, reasoning, and social engagement, all of which help stave off the adverse effects aging can have on the brain. After retirement, there is often a decline in older adults’ cognitive abilities (Xue et al. 2018).” Same as previous comment. With side effects like these it seems like you would have to force people to retire.

- “In addition to the benefits derived from increased social interactions, for many people, life derives some meaning, purpose, affiliation, and structure from the fact that they are working.” Again, I have no idea why people would retire and give all of that up.

Ok, enough with the point-by-point issues. The overarching problem with this paper is that most people will confuse correlation with causation. In fact, I think the causation likely runs the opposite direction. I will stipulate that people working in retirement are doing better financially, cognitively, socially, etc. I would also bet a reasonable amount of money that older people who are doing better financially, cognitively, socially, etc. are more employable, able, and willing to work, etc. I think the causation runs from the ability to the work rather than from the work to the ability. This is borne out in other research which shows that most “retirement” is involuntary. In fact, the median expected retirement age is 65 but the median actual age is only 62. (Of course, many Baby Boomers expect to work “forever” because they haven’t saved any money.)

Working longer is a terrific thing to do, but a terrible thing to rely on!

Fifteenth, it is interesting how culture is reflected in tax codes. There is a funny twitter thread on it here.

Sixteenth, good article: Academically Verified Investment Strategies that Failed. I think the title is overstated, but it is important to realize that even the best investment strategies only work on average. People tend to take “on average” to mean “always, given enough time” and their “enough” is way, way, way too low.

Seventeenth, I directed your attention to both of these papers (one, two) when they first came out. But the first half of this post is a good, clear, review of the point that most stocks underperform not just bonds, but t-bills. Worth reading.

Eighteenth, I covered this in a newsletter to clients, but this list is broader so I thought it was worth sharing here too. I thought this article was interesting (but not original, see here, and I wrote about the ratio in a newsletter to clients back in 2004).

I tend to use net worth as my one number. I think one significant limitation he leaves out is TVM. Someone who saves a fixed percentage of income but has high earnings early and low earnings late will show a much better LWR than someone who has the reverse (assuming positive returns on the investments from the savings).

Nineteenth, investing is hard, because you need to answer these questions:

- Am I being disciplined or stubborn?

- Am I being foolish or staying ahead of the curve?

- How useful is market history?

- What if it really is different this time?

- Do I have enough?

See also:

As Voltaire observed, “Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.”

Twentieth, here are a few value links:

And a few on whether our definition of value should incorporate intangibles:

DFA, as usual, is fighting a rear-guard action and claiming that nothing has changed and they will determine “value” using price-to-book (with no adjustments for intangibles) as the good Lord intended and the high priests Fama and French decreed in the beforetimes.

Twenty-first, here is a good graphic about Agile vs. Traditional management:

The smaller the organization (team, company, department, whatever) the more agile it probably is by nature. As the size increases it becomes more difficult to keep that agile spirit. I’ve often said that organizational problems rise with the square of the number of people involved.

Similarly, Principal put out a piece describing how they pick stocks with high ownership by the operator. I’m not sure about the investment thesis, but the points are good business points that can help us manage our firms. Here are the operational items owner/operators do differently (or better). My wording and interpretation of their points:

- Decentralization, avoidance of bureaucracy, aligned incentives

- Conservative management designed to weather storms rather than maximize short-term revenue

- Customer orientation

- Productivity over polish or substance over form

- Frugality

- Long-term orientation

Twenty-second, tap your credit lines quickly in a crisis because, “Credit line cuts are concentrated on borrowers who do not use credit lines...” (source)

If you have a line tapped the bank is scared to call the loan and potentially create a bad debt (the last thing they need more of in a financial crisis), but if it isn’t tapped they need to reduce their potential balance sheet growth. (The loan – from the bank’s perspective – is an asset. If their assets are growing, but their equity is fixed – or declining – they could fall short of required capital ratios.)

Twenty-third, emerging markets are changing.

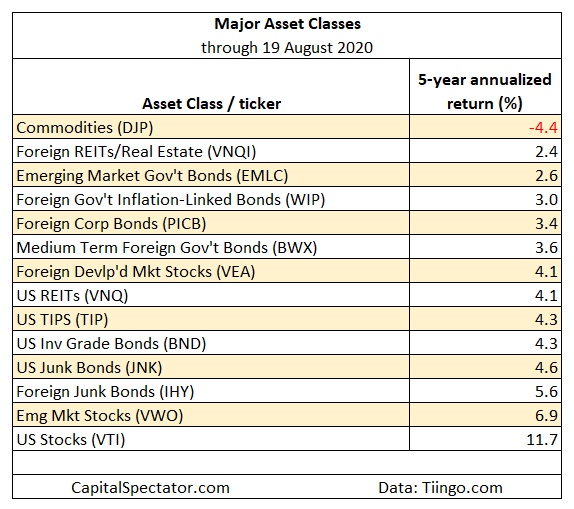

Twenty-fourth, I saw the table below and was struck that between the items on the ends there is a large gap to the next item. In other words, the largest gap in performance within the items not best and worst was 130 bps (and most gaps are far less than that). But there is a gap down to commodities of 680 bps and up to VTI of 480 bps.

Twenty-fifth, from Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice, we have this great financial planning (and business) advice (source):

When making decisions, instead of asking ourselves which option will give us the best results, we should be asking which option will give us good-enough results under the widest range of future states of the world. Instead of trying to maximise return on investment in our retirement account, we should be setting a financial goal and then choosing investments that will allow us to achieve that goal under the widest set of future financial circumstances.

Twenty-sixth, I plan to flesh this out in a future newsletter and blog post, but I think there are just two key factors that lead to success:

- Internal locus of control

- Long time-horizon

People who have more of those two things will be more successful on average. Those that don’t will find it very difficult to be successful.

I’ll expand on the second one here, because I think it is underappreciated.

Consider a few things that we would consider mistakes (or at least pretty suboptimal):

- Carrying credit card debt at 18%

- Not contributing to a retirement plan (not even for the match)

- Getting a big screen TV from the Rent-A-Center to watch the playoffs

- Not continuing an education

- Working a “dead-end” job (and complaining instead of actively working to get to a better one)

- Marrying a spendthrift (but they are fun!)

I would submit that all of those are actually GREAT financial decisions – if the universe ends on Tuesday. They are only bad decisions if it doesn’t.

Once I got this, it explained a lot of decisions that people make that seemed really dumb to me. They aren’t dumb necessarily, they just have a very short time horizon. You can equate this to discount rate too. A short-term horizon is the same as a high discount rate. If someone has a 30% discount rate, then 18% credit card debt is a screaming deal. If someone has a 3% discount rate, then paying down on a mortgage at 4% is a great deal.

Now, obviously, there are life situations where people are hindered from continuing their educations, etc. more than others but ceteris paribus short-term thinkers will do the things on that list and long-term thinkers won’t.

So, I think successful people prioritize the long-term over the short-term. That means, all else equal, they would have higher savings rates and higher education rates because those are terrible short-term decisions and great (usually) long-term decisions. The famous marshmallow test is on this same point of time horizon correlating with future success.

Now the obvious rebuttal is that some people can’t be long-term thinkers because of their impoverished situation. I don’t think that is usually true, though it may be for brief periods, but if the poverty is perpetual, I think the causality probably runs the other way. I wrote about this in a blog post on financial success. It’s pretty strident, but I think it is true.

There are only a few things folks need to do to be financially successful (see here). They aren’t hard conceptually, but they are hard operationally.

As Morgan Housel says, “The only way to build wealth is to have a gap between your ego and your income.” Some people, groups, families, etc. have bigger gaps. Too many folks at the bottom end of the wealth spectrum have a negative gap (they spend more than they make). If someone has low income and has only managed to accumulate a small amount of net worth, then I have (depending on the situation) some sympathy. But many families in the U.S. have a net worth of approximately zero (even, in some cases, with good incomes). That’s not even trying.

The other issue, I think, is that in some families/cultures/etc. if an individual makes good decisions and does well financially, they are expected to “share the wealth” with those who made poor decisions and aren’t doing well. If you work hard and succeed only to be no better off because of all the folks who will expect you to support them, you might as well not work hard (see failure of communism). (On the other hand, knowing there is family/community/government support can facilitate risk-taking so this isn’t necessarily a clear-cut issue.) My brother once lived in a country where if someone got a bonus or some other windfall, they would literally have to buy something with it on the way home (big screen TV, for example) for “the family” (but really for them) or else they were culturally required to share the money with all their relatives. That removes work incentives pretty thoroughly. This goes to the “locus of control” I mentioned at the beginning. Your financial success is outside your control because of the other folks with a moral demand (from that cultural perspective) on any success.

Twenty-seventh, a great list of financial and economic data sources.

Twenty-eighth, this is great: Blockchain, the amazing solution for almost nothing.

Twenty-ninth, an article on life insurance shenanigans, here.

Thirtieth, here are the states that have transfer taxes at death:

Thirty-first, I have said since at least 2014 that there is 1) no risk-adjusted size premium, though 2) it is an amplifier to factors such as value and momentum. This paper comes to the same conclusion: “We conclude that size is weak as a stand-alone factor but a powerful catalyst for other factors.”

Thirty-second, I have been thinking about wealth taxes that have been proposed and it occurred to me that we already have a few of them (property taxes are one, I’ll get to the other below) but we don’t think of them as wealth taxes. That led me to think about some other illogical tax items. This is just about the items related to capital gains; I may or may not go on to other topics later.

I wrote up some reform ideas a few years ago here and here but this is new.

Here are a few oddities just to illustrate some problems. Let’s assume that inflation is 3% (and always was); long-term capital gains rates are 20%; short-term capital gains/ordinary income rates are 40%; and corporate tax rates are 25%. The numbers aren’t really important, but I want to be able to do some simple examples with nice easy round numbers that are close to what exist though not exact (state taxes, Medicare surcharges, brackets, etc. would all change them for various taxpayers anyway).

- Situation 1: Taxpayer Alpha bought Stock X 20 years ago for $100,000 and it has grown at an average compounded rate of 3%. Since inflation has been 3% the real wealth has not increased. Nonetheless, if sold the taxes would be about $16,000 [($100,000 * 1.03^20 - $100,000) * 20%]. This is a wealth tax basically set at the rate of inflation times the tax rate (so in this case 3%*20%), but only collected upon disposition so there are some compounding differences. Our taxpayer, in purchasing power, is $16,000 poorer. We have had low inflation for so long I don’t think people appreciate the damage that income taxes combined with inflation do.

- Situation 2: Taxpayer Alpha dies and leaves Stock X to Taxpayer Bravo. There are no taxes. (Step-up in basis.)

- Situation 3: Company X pays a special dividend (qualified) of $80,000. Taxes would be $16,000.

- Situation 4: Taxpayer Charlie buys Stock Y one year ago for $100,000 and it is now worth $180,000 (roughly the same as the previous example). Since it has not been a year-and-a-day, sales would result in taxes of $32,000.

- Situation 5: Taxpayer Delta buys Stock Y one-year-and-a-day ago for $100,000 and it is now worth $180,000. Sale would result in taxes of $16,000.

You get the idea, the first three situations are economically identical, yet the taxes are different. Worse, there is no actual (real) gain, yet taxes are assessed. This is why using qualified plans/IRAs, Roths, etc. is so vital. That is the only way to avoid paying taxes on phantom (inflation) gains. (Assuming all qualified plans/IRAs are exclusively funded with pre-tax dollars.) The last two situations are nearly identical, but the taxes are wildly different.

So here is my modest proposal. All of these should be adopted simultaneously, not in isolation, they work very well together, not nearly as well individually. I’m not trying to minimize (or maximize) taxes, I’m trying to make the economic reality of a situation give rise to appropriate taxes. Anyway:

- All income tax rates for a given taxpayer should be the same marginal rate, no special long-term capital gain or qualified dividend rates. This eliminates the “gaming” that is sometimes done to turn earned income into a capital gain (carried interest for example). This would raise tax liabilities. (But stay with me, it gets better.) A flat tax would be even better, because the sale of large value items (real estate for example) could kick someone into a higher bracket than they would normally be in.

- Companies should get a corporate tax deduction for dividends paid. This removes the tax incentive to use debt rather than equity. It also means that the rationale for a special dividend rate to compensate for double taxation is removed. (Under current rules/rates above a company makes $20, pays 25% in taxes leaving $15, pays it out in a dividend taxed at 20%, the taxpayer nets $12. With my change, the company makes $20, pays it out in a dividend and it is taxed at 40% leaving the taxpayer the same $12.) This would lower tax liabilities to the company. (It would also incent management to distribute earnings rather than horde them and empire-build.)

- Step-up in basis on death should be eliminated. Carry over basis eliminates the economic dislocation from holding property that would otherwise be sold, waiting for the owner to die to avoid tax and leave the heirs more. This would raise tax liabilities. It also, given that we have a progressive tax structure, aligns taxes with the economic situation of the heirs. A “starving artist” heir would pay little or no taxes, a neurosurgeon heir would pay much more. That seems fair.

- Since we have eliminated the step-up in basis, we can eliminate estate taxes now too. That would raise taxes, but it would also free up many very expensive tax attorneys and CPAs to do something socially useful. This would lower tax revenue.

- Investment assets held longer than a year have the basis indexed for inflation. So there is no more tax on growth that isn’t real. The stock bought for $100,000 that grew to $180,000 over 20 years at 3% inflation would have no tax due. A 20-year bond bought for $100,000 with 3% interest (remember inflation is 3% too, so this is zero real return) would have taxes on the 3% paid each year (at 40% rate). But upon maturity, the bonds would have a capital loss equivalent (roughly, you have compounding issues again) to the interest paid. So the taxpayer, having received no real return, pays (roughly) no tax. This structure means that the effective tax rate on stocks is still a little lower than bonds given that dividends are usually lower than interest so you are ahead on the time value of money, particularly on growth stocks, but then the company didn’t get a deduction if they had earnings. This would reduce tax revenue.

- Repeal the $3,000 limit on taking losses against ordinary income. Since all the rates are the same there is no point to this. (And it means the bond buyer in the earlier example, can actually use the real loss upon maturity.) This would reduce tax revenue.

- Section 121 can be repealed (the home sale exclusion of $500,000/$250,000). Since we are indexing to inflation everyone only pays taxes on real appreciation. The current method penalizes people who 1) buy expensive homes (the “free” appreciation is in dollars, not percentages), and/or 2) don’t move. If I buy homes for $1,000,000 and move every five years I will probably never pay taxes on it. If I buy a home for $500,000 and don’t move for 30 years I probably would. That seems … odd. This would probably raise tax revenue, but it could conceivably go the other way. I don’t have data (and behavior would change).

This is just a guess, but I think doing all of that probably wouldn’t materially alter taxes paid (in aggregate) but it would remove a lot of uneconomic behavior that people engage in for tax reasons.

Of course there is zero chance of this being cleaned up logically…

Thirty-third, a great quote, “Save like a pessimist, invest like an optimist.” (Morgan Housel again)

Thirty-fourth, a paper: Putting 2020 into Perspective: Diversification May Work Better than You Think.

Thirty-fifth, the ESG section of this is excellent. See also this, and Malkiel hit ESG (one of his points is the same as in the paper) in the WSJ as well. This was outstanding too. In my writings I tried to make the same points but the paper is more elegant (Risk-Return ESG vs. Collateral Benefits ESG is way better than my good/bad vs. virtuous/evil terminology). Finally, we have this.

Thirty-sixth, following is a portion of something we sent clients recently:

While many are concerned about the election, remember how your preferred source of news was in histrionics in prior elections when “your pick” lost. The republic survives!* Here are the total returns of the U.S. market (I’m using the Vanguard Total Stock ETF as the measure) from election day to election day (or 9/30 for this year) over the past few cycles:

From |

To |

Annualized Returns |

11/4/2008 |

11/6/2012 |

12.5% |

11/6/2012 |

11/8/2016 |

12.8% |

11/8/2016 |

9/30/2020 |

14.2% |

Missing any of those returns because of worries about the White House occupant would have been very costly.

_____

*I initially wrote, “And yet it moves!” but I thought the reference was perhaps too obscure. It is what Galileo is reputed to have said sotto voce after being forced to recant his (correct) claim that the Earth orbits the Sun. It seemed apt because it feels as though the inquisition (figuratively) would be unleashed on anyone who publicly acknowledged that the world – and the markets – will almost certainly be fine regardless of the election winner.

Thirty-seventh, here are the answers from the question above:

Asset Class |

CAGR 7/2000-6/2020 |

US REIT |

9.00% |

Foreign REIT |

7.89% |

R2000V |

7.65% |

EM |

6.93% |

HY |

6.80% |

R2000 |

6.69% |

R3000V |

6.42% |

R1000V |

6.32% |

R3000 |

6.15% |

R1000 |

6.10% |

60/40 |

5.92% |

S&P 500 |

5.91% |

TIPS |

5.47% |

R3000G |

5.46% |

R1000G |

5.45% |

40/20/40 |

5.45% |

R2000G |

5.34% |

AGG |

5.14% |

EAFE |

3.37% |

How did you do? I’ll bet you didn’t have REITS as first!

I threw in 60/40 (S&P 500/AGG) and 40/20/40 (S&P 500/EAFE/AGG) for comparison. You can see that a properly diversified, though naïve (meaning simple, not simplistic), portfolio (the 40/20/20) has been pretty bad over the whole period.

Observations of possible interest:

- 60/40 beat 100/0 over a twenty-year horizon. Stocks for the long run? Perhaps not, at least not only stocks. (Barely, but still.)

- Despite recent underperformance, small value has still been the winner over the whole period (REITS are a flavor of small value too).

- HY has done better even than stocks despite decimation in the GFC. Given the negative skew on the asset class, that is surprising.

- EM has been wonderful, but EAFE terrible.

Finally, my recurring reminders:

J.P. Morgan’s updated Guide to the Markets for this quarter is out and filled with great data as usual.

Morgan Housel and Larry Swedroe continue to publish valuable wisdom. Just a reminder to go to those links and read whatever catches your fancy since last quarter.

That’s it for this quarter. I hope some of the above was beneficial.

If you are receiving this email directly from me, you are on my list of Financial Professionals who have requested I share things that may be of interest. If you no longer wish to be on this list or have an associate who would like to be on the list, simply let me know.

We have clients nationwide; if you ever have an opportunity to send a potential client our way that would be greatly appreciated. We also have been hired by some of our fellow advisors as consultants to help where we can with their businesses. If you are interested in learning more about that arrangement, please let us know.

We also offer a monthly email newsletter, Financial Foundations, which is intended more for private clients and other non-financial-professionals who are interested. If you would like to be on that list as well, you may edit your preferences here.

Finally, if you have a colleague who would like to subscribe to this list, they may do so from that link as well.

Regards,

David

Disclosure

|